Two things are very important to me:

- Documenting my workflows.

- Sharing my knowledge with others as freely as possible.

As of time of writing, I’m participating in some “learning sprints” for queries in Logseq. I actually don’t consider myself a Logseq power user or anything, at least compared to the folks who build these complicated dashboards and workflows for every aspect of their lives. I mainly use Logseq for my Zettelkasten; therefore, my needs aren’t too complicated.

I wanted to write this post now because the sprint has me thinking of how I use properties, tags, and links within my Zettelkasten, and how that affects queries. Also, vice versa.

I hope a walk-through of my setup and workflow is helpful. If you have questions or comments, please reach out to me! My Twitter is linked on the main page of this site.

Alright, let’s get into this.

Let’s get on the same page

Any time I write about a topic which has commonly misunderstood or slightly variant meanings, I like to explain how I’m viewing it. The Zettelkasten as a topic and method means a lot of different things depending on who you talk to about it. Without getting into who’s right, who’s wrong, gatekeeping, the history, etc. etc., here’s how I understand the Zettelkasten.

Zettelkasten

German word meaning “slip box.” These are apparently very common over there. The general method has been around for centuries, but now, we mostly interact with Luhmann’s practice. And to be more precise, we’re interacting with that mostly through the book How to Take Smart Notes by Sönke Ahrens.

A Zettelkasten, either analog or digital, has multiple “compartments” for different kinds of notes. Usually, there are compartments for reference notes and “main” notes, with the occasional project note, structure note, and so on.

A person takes whatever “fleeting” notes made through the day (more on those in a second) and writes “permanent” notes from them. A person will also create reference notes for sources (like books, articles, movies, and conversations), and they will make notes inspired by/in response to those sources. It’s important to connect notes together.

As notes accumulate, webs and clusters emerge. Those clusters help inform writing projects and other forms of creative expression.

The way I understand and do the Zettelkasten method is focused on developing ideas for writing, not general note-taking, knowledge management, or linked tool environment dashboard system thing.1 If you use it that way and it works, don’t let me stop you.

Fleeting Notes

Fleeting notes make up most of the notes we take during the day. These are our tasks, random lists, thoughts, and ideas. They are not necessarily meant to be permanent; instead, you review them and see what you can bring into your Zettelkasten.

Permanent Notes

Permanent notes are the notes that make it into the Zettelkasten. At least in the way Ahrens uses the term, a permanent note is not synonymous with a “main” note. All “main” notes (or Zettels as some of us call them) are permanent notes, but so are literature notes.

Permanent means it stays in your Zettelkasten.

Reference Notes

I think Ahrens calls these literature notes. I follow Luhmann’s method and reason for making these notes, so at their simplest, they are bibliographic entries in my Zotero database and nothing more. If I’m going to take notes on them, I will make highlights, but instead of necessarily rewriting anything in my own words or summarizing what I’m reading, I make a simple index. I note the page something is on, I give a brief hint as to what it’s about, and then I tag it with a topic I’m focused on.

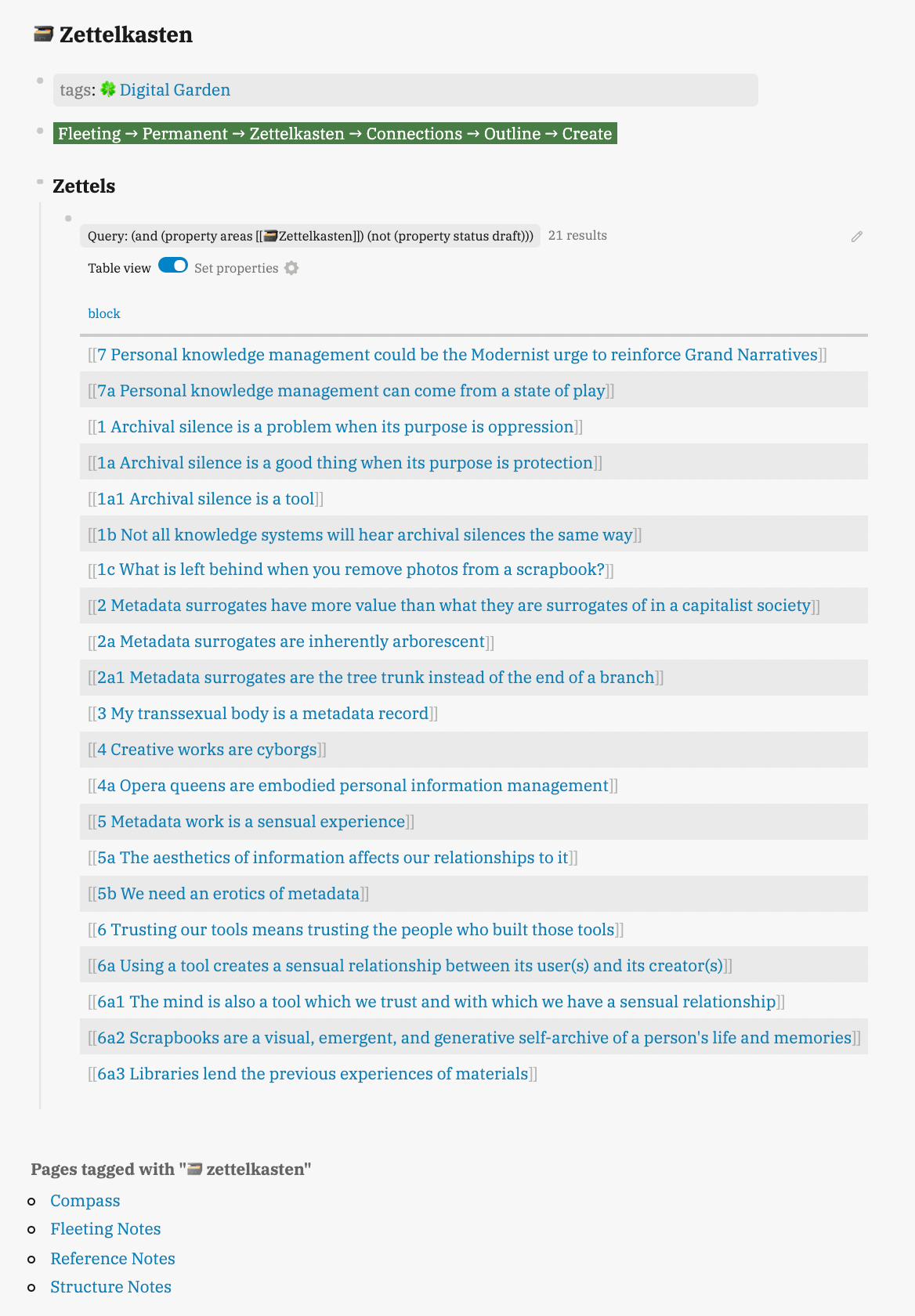

Zettels

Zettels are the main part of the Zettelkasten. For me, these are not about rewriting something I’ve learned in my own words. Rather, they are for responding to, building on, or otherwise interacting with a source or idea.

My digital Zettelkasten

Why my setup is so weird

Like I’ve mentioned elsewhere, I do all my Zettelkasten nonsense in the tool Logseq. Logseq is an outliner tool with a focus on the block instead of the page. I see a lot of folks who do Zettelkastens (or Zettelkästen if we’re being pedantic) in Logseq leaning heavily into the outliner aspect and nesting blocks for their Zettelkasten structure. I would love to do that! However, I publish my Zettelkasten online via the Logseq plugin which converts public pages to Hugo-compatible markdown. I don’t think the nesting approach works well in my use case.

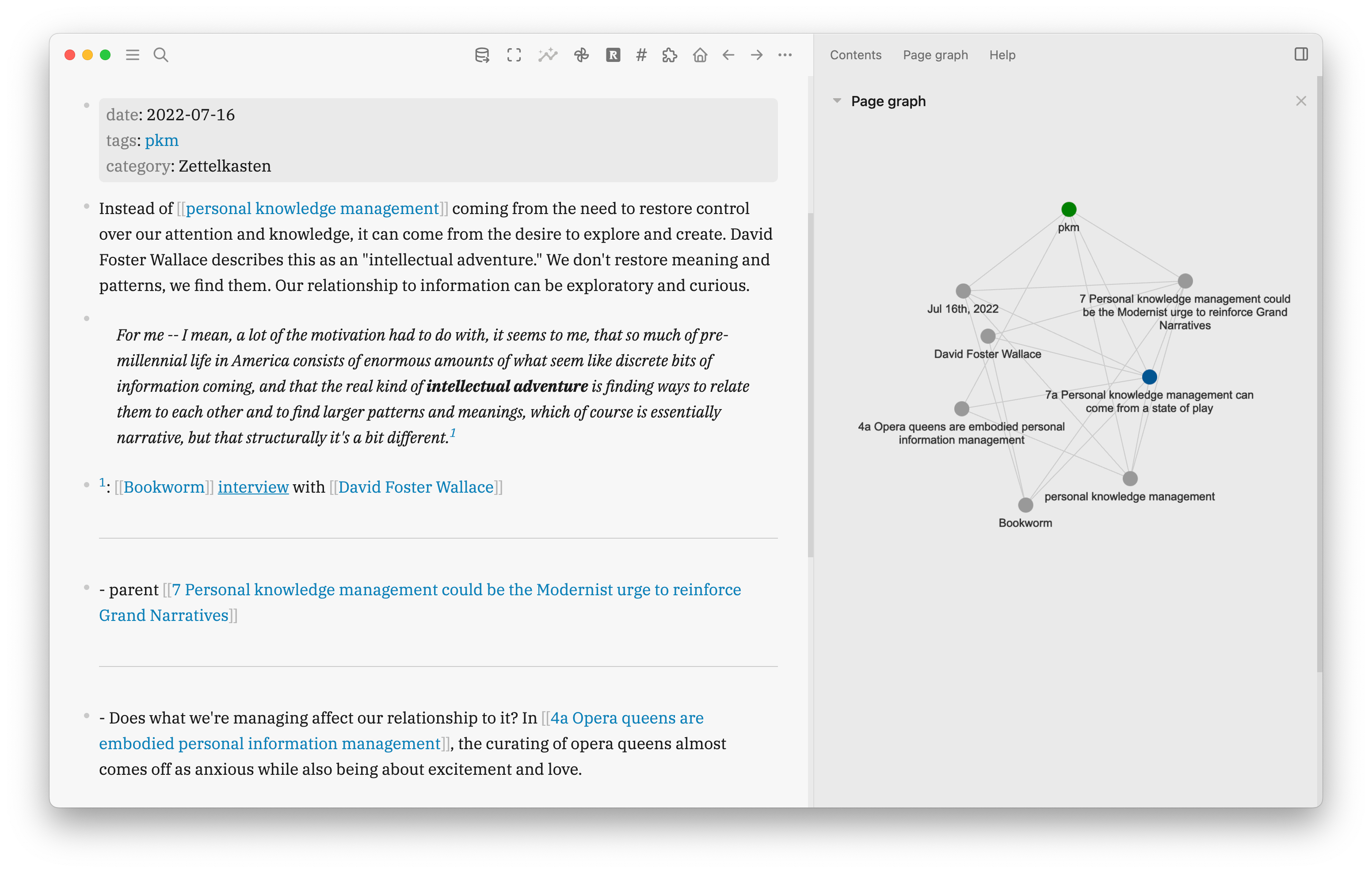

I also care a lot about the visual representation of my graph database. I promise I’m not a person who is obsessed with making their graph visualization look as cool as possible (more power to y’all who do). I just like seeing the clusters in my Zettelkasten form, and that visual representation is an easy approach. This means I don’t need giant nodes in the network visualization for tags and pages that are acting more like folders than anything. I also don’t want to see a lot of connections between notes that aren’t in support of the Zettelkasten.

My solution is to rely heavily on blocks in my daily journal page. When you insert tags and links in a block, that connection won’t be reflected in your graph visualization unless you include journal pages in the settings.

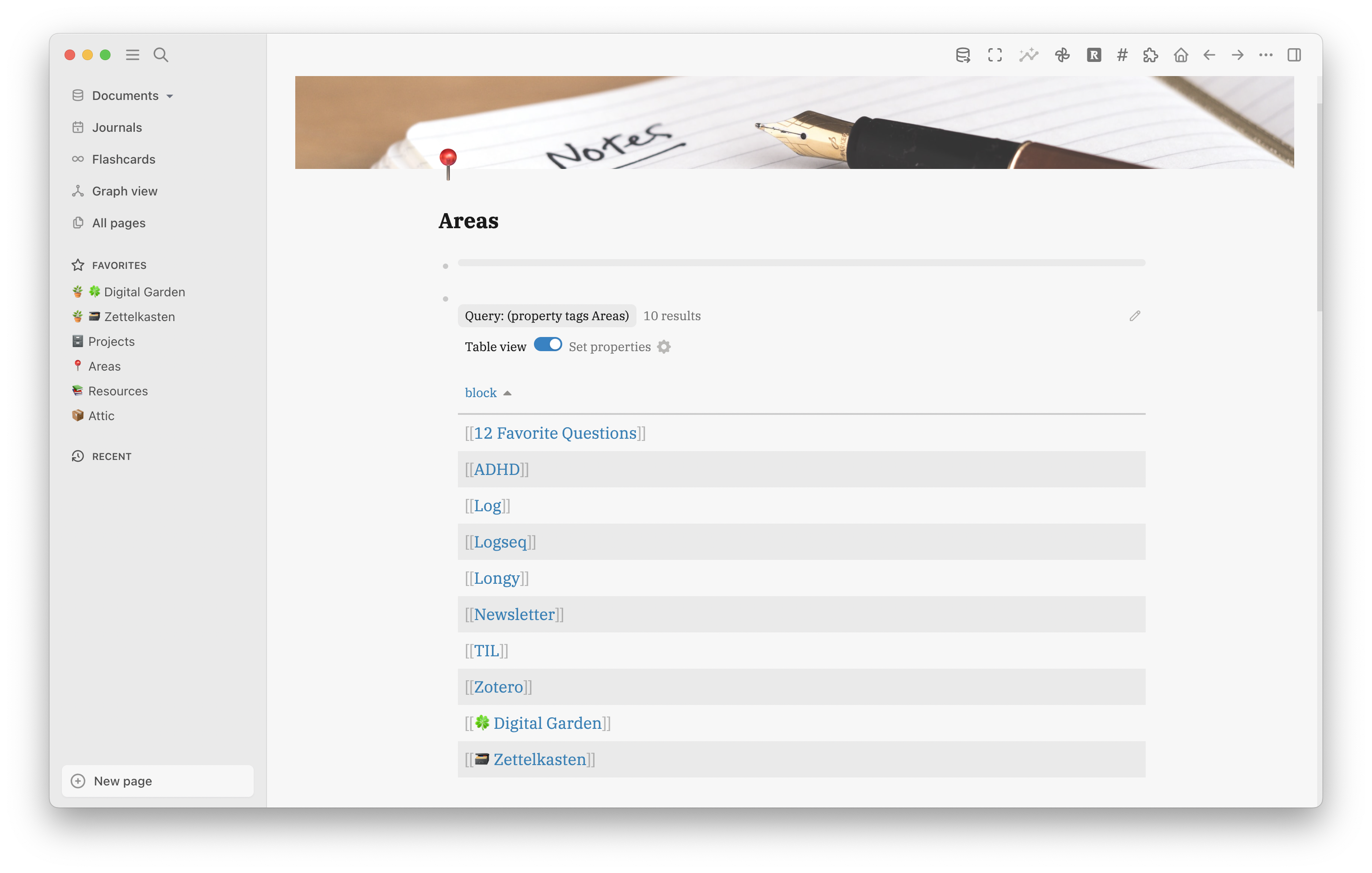

How does this fit into PARA?

Remember how I did that whole Building a Second Brain thing?2 The organization framework taught in that is called PARA: Projects, Areas, Resources, and Archives.3 Because some folks view the Zettelkasten as another “second brain” system, they try to “PARA” their Zettelkasten.

However, while a Zettelkasten can be part of a “second brain,” it in and of itself is not the same thing, at least not in the way Tiago Forte teaches the second brain. I include my Zettelkasten in the Areas section of my second brain organization because it’s something I need to maintain.

Step 1: Fleeting Notes

The first step in my Zettelkasten workflow is taking fleeting notes. As defined above, they’re basically any notes I take during the day. Like I said, reminders and tasks are technically fleeting notes.

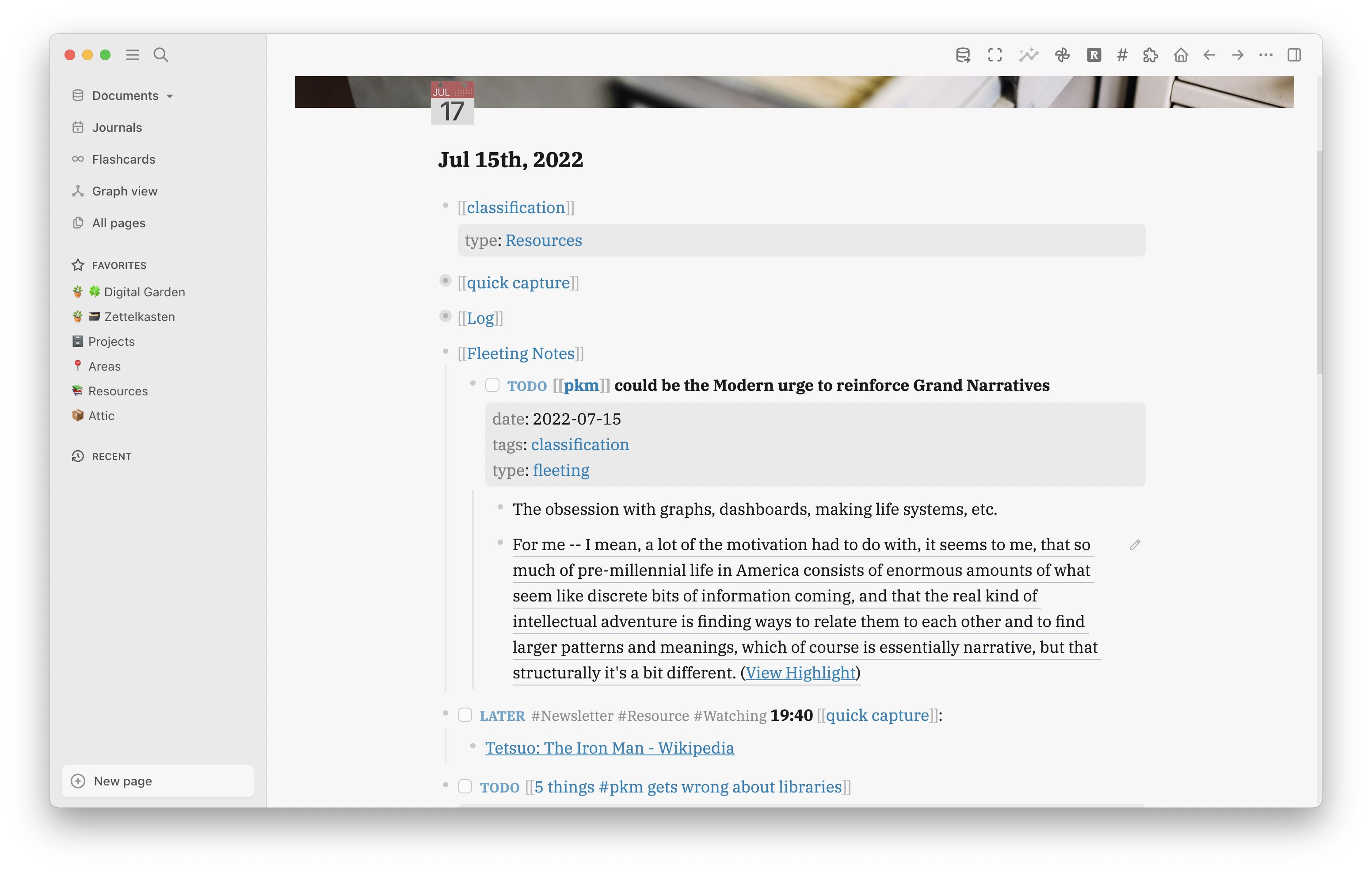

In Logseq, I have a template for the fleeting notes I know will feed into my Zettelkasten. Usually, these are ideas for Zettels.

- TODO **Note goes here**

date::

tags::

type:: [[fleeting]]

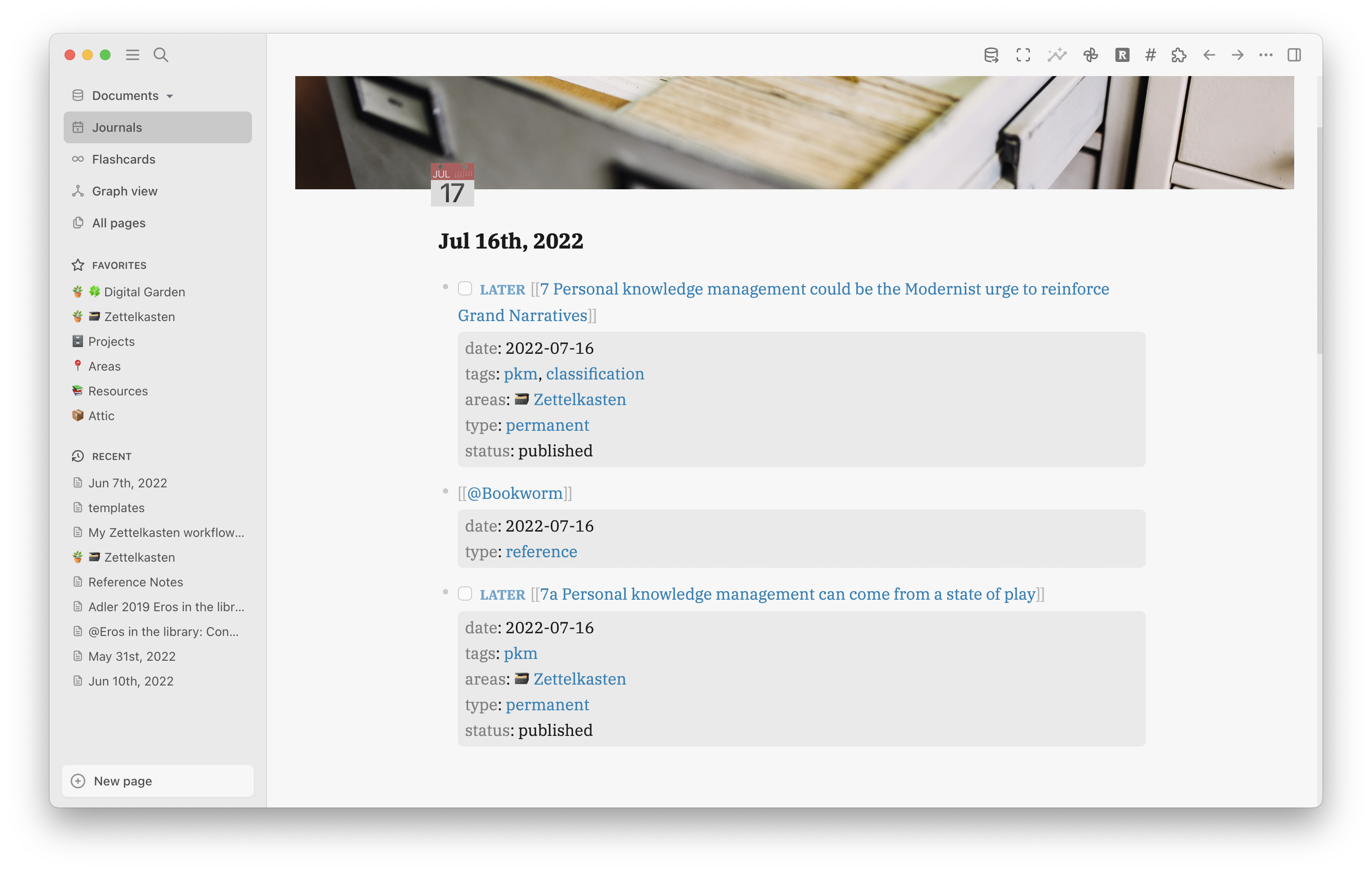

I work from my daily journal page. I create a block and use the above template. In practice, it looks like this:

The reason why Logseq is a great tool for me is that I don’t have to create a page for each fleeting note. They can all be blocks, and those blocks can be queried, referred to, and embedded elsewhere.

So, let’s go through each aspect of the above fleeting note.

First, you’ll notice I have a TODO task marker on it. I don’t use Logseq for task management; however, I mark these specific fleeting notes as TODO to remind me that they are actionable. These notes aren’t just thoughts. They are something I can grow, and I shouldn’t let them slip by.

Next, you’ll see the note has block properties. Instead of doing inline tags or links, I do properties to make querying easier.

The first property is the date property. I don’t use the Logseq date picker for that or insert a linked date there. I manually type the date in YYYY-MM-DD format. I do this because, when I query my fleeting notes, I can view the results as a table and sort by date. If I were to use the date picker, the format for the above note would be “Jul 15th, 2022.” That, obviously, won’t sort chronologically.

Then I have tags. Pretty self-explanatory. These are the topics I think relate to this note.

Finally, I have the type property with the value fleeting.

After I do my block properties, I make child blocks to insert quotations, related notes, further context, etc.

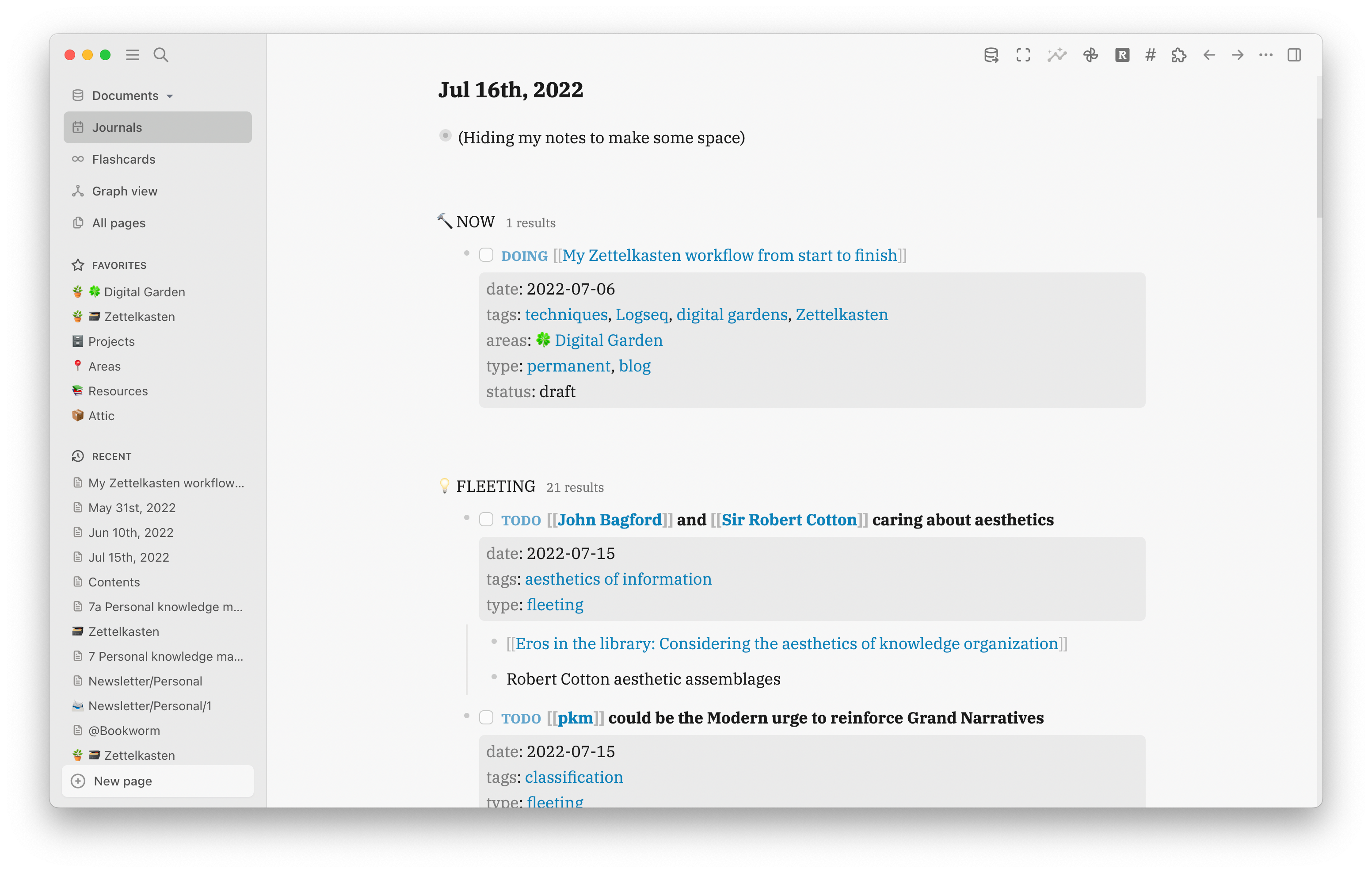

I keep mentioning that I query these fleeting notes. What I do is insert the following query in the default queries section of config.edn:

{:title "💡 FLEETING"

:query (and (property type fleeting) (not (property template)) (not (task done)))

:collapsed? true

:breadcrumb-show? false

:result-transform (fn [result]

(sort-by (fn [h]

(get-in h [:block/properties :date])) > result))}

This query creates a section in my daily journal page called FLEETING (with a cute lightbulb emoji). It looks for all blocks that have the property key type with the value fleeting. I don’t want my template to show up, so I tell it to exclude the property key template. And because I only I want fleeting notes I haven’t acted on to show up, I tell it to exclude any blocks with the task marker DONE. I also tell the query to collapse the results and not to show the “breadcrumb trail” of where the block comes from.

The tricky part is having it sort my notes by date. I have it get the property date, and the greater than symbol > makes it sort with the newest notes at the top. I might play around and do it the other way so I see my oldest notes first.

Default queries are inserted into the current daily journal page (but not previous daily journal pages). The default queries that come with the default config.edn are the NOW and LATER queries. Here’s what those queries and my FLEETING query look like in action (I’ve uncollapsed the FLEETING notes):

Also Step 1: Reference Notes

Often, I’ll make fleeting notes in response to something I’m reading, watching, listening to, etc. In that case, I’ll make a reference note for whatever resource it is. Sometimes, I’ll do this first because I’m reading something I know is related to a current interest of mine.

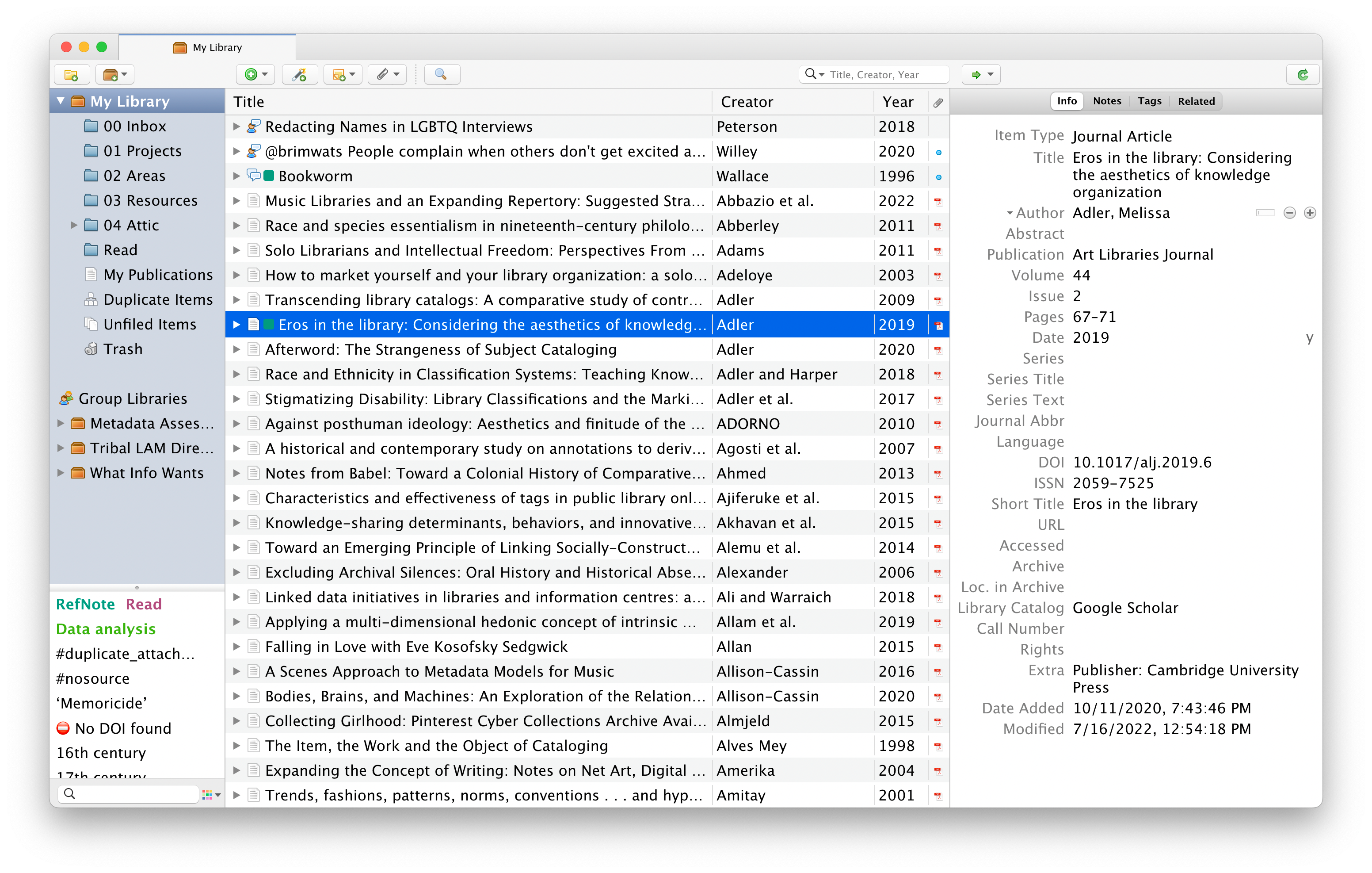

Reference notes start as entries in my Zotero library.

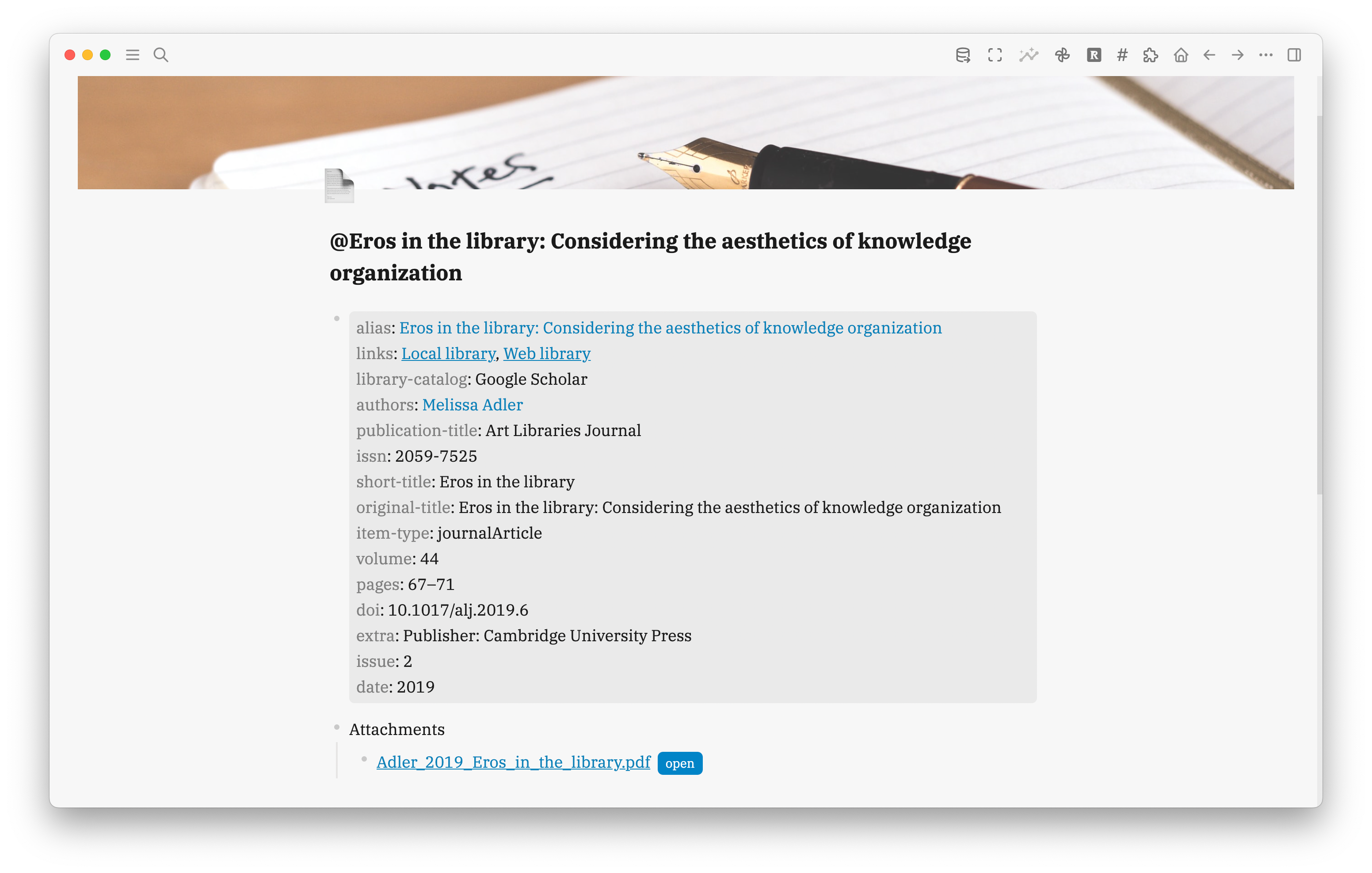

Then, for resources I know I’m going to make notes from or cite, I create a page for it using Logseq’s Zotero integration.

Sometimes, I leave it at that. Usually, this happens if it’s one quotation from the source I’m using, or it’s short or familiar to me already.

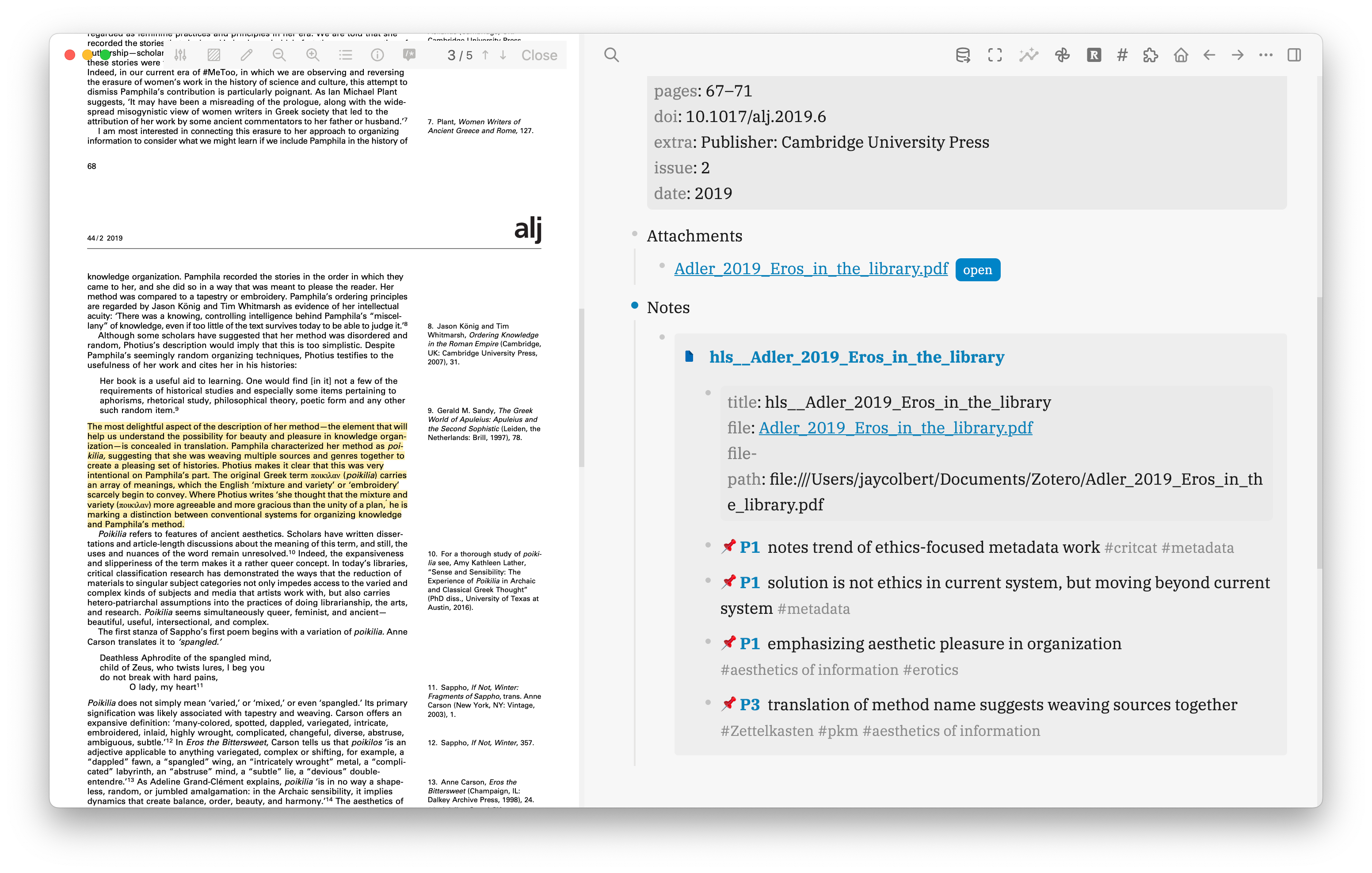

If it’s something like a journal article, a book, or any type of resource I want to dig deeper into, I take notes on this page. If there’s a PDF, I take notes by using Logseq’s PDF reader. When I highlight passages in the PDF, an annotations page is created with the text of each highlight; each block in that page is actually a block reference to the highlight in the PDF.

Instead of taking lengthy notes and summaries, I create an index when I read. That index is guided by what I’m actively interested in at the moment. I’m not creating a general index of the resource. When I take a highlight, I can actually change the text in the block that’s created. I mention briefly what the highlight is about, and I tag it with a topic. The text is usually themed around that topic. If I were reading with a different topic in mind, what I write for that highlight might be different.4

I embed the highlights page under a Notes block in my reference note.

I create all reference notes from the daily journal page. I technically have a template for it, but really, all I do is give it a block property of type:: [[reference]] and the date, like I did for fleeting notes. Sometimes, I’ll assign tags.

- insert reference here

date::

tags::

type:: [[reference]]

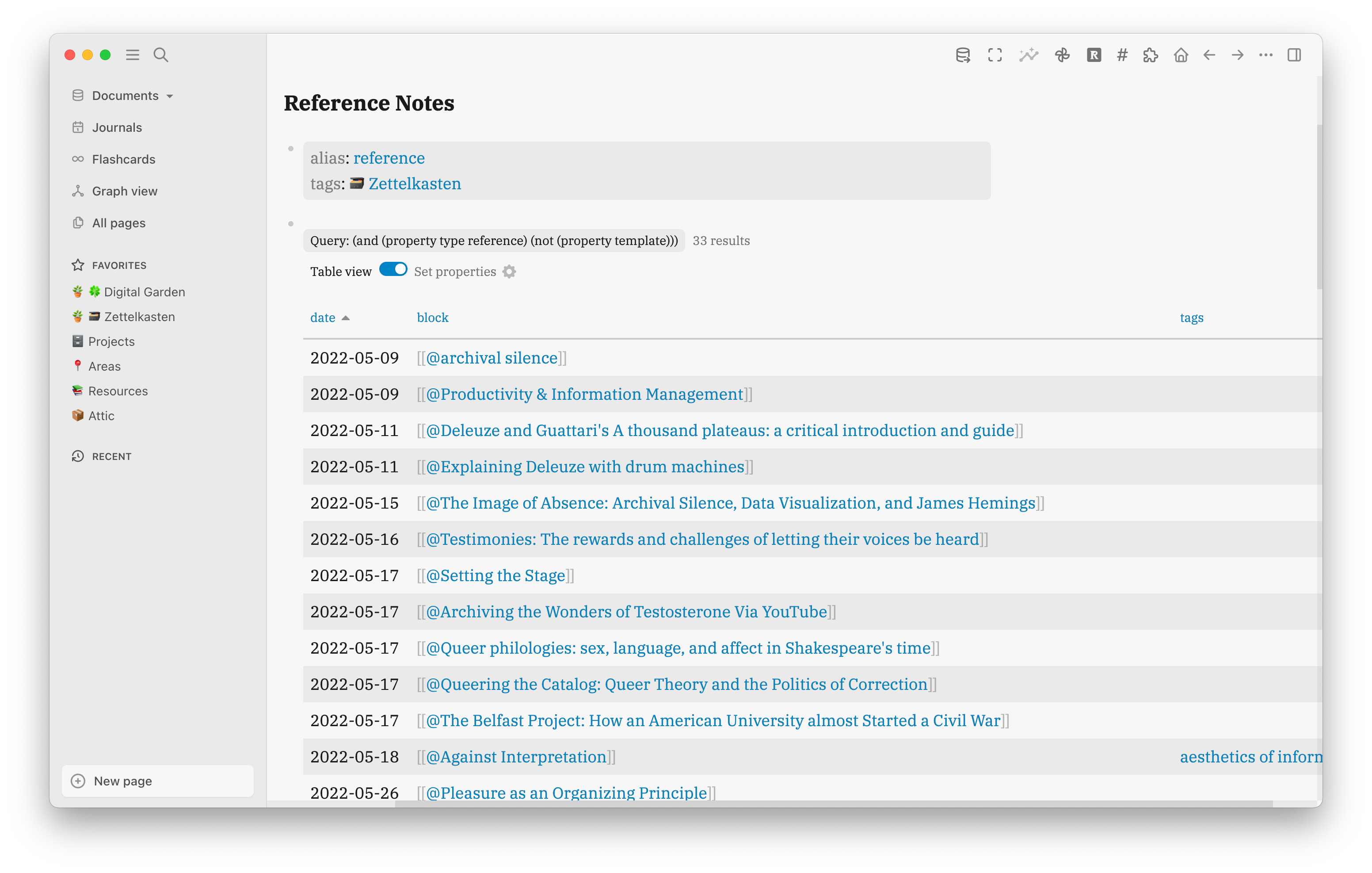

I have a page titled Reference Notes where I query all my reference notes.

I use this query:

{{query (and (property type reference) (not (property template)))}}

Step 2: Zettel Time

Time to write some notes!

As with everything else, I create the permanent note from the daily journal page using the following template:

- LATER [[]]

date::

tags::

areas:: [[🍀 Digital Garden]], [[🗃 Zettelkasten]]

type:: [[permanent]]

status:: draft

Let’s break this down.

I give it the task marker LATER so I can query it in my Newsletter workflow; the query for that will make the block disappear when I mark it DONE. My workflow and queries are inspired by Ramses Oudt:

After I publish my weekly newsletter, I remove the LATER from the original block.

Then I create the page. I use an alphanumeric system at the beginning of my note titles because I’m following a Folgezettel structure.5 A Folgezettel is a “follow-up note.” A Zettelkasten is [[rhizomatic]] and non-hierarchical, but you can indicate trains of thought or a cluster about a topic by using Folgezettel. I’ll use some recent notes to demonstrate.

You’ll see two Zettels there: 7 Personal knowledge management could be the Modernist urge to reinforce Grand Narratives and 7a Personal knowledge management can come from a state of play. The 7 doesn’t mean any particular thing except that it wasn’t directly related to the previous 6 topics. 7a means it’s a follow-up to 7.

After the alphanumeric indicator, I write my actual title as a statement.6 Then I do all the standard block properties we’ve been doing, like date and tags. For areas, this template has both 🍀 Digital Garden and 🗃 Zettelkasten; I only use one depending on the type of permanent note. In this case, I’ll remove 🍀 Digital Garden. For type, this is a permanent note. The status is draft until I finish it.

Just like with my fleeting notes, I have a default query that shows me all my drafts in reverse chronological sort:

{:title "📝 DRAFTS"

:query (and (property status draft) (not (property template)))

:collapsed? true

:breadcrumb-show? false

:result-transform (fn [result]

(sort-by (fn [h]

(get-in h [:block/properties :date])) > result))}]}

Now I can go into the page I just created. I have a template I use for all my Zettels:

- date::

title::

tags::

category:: Zettelkasten

- Zettel goes here.

- > source[^1]

- [^1]: Source goes here.

- -----

- - parent

- -----

- - I think this note relates to this other note.

For date, I do YYYY-MM-DD because that’s what is needed for the Hugo static site generator and theme I use. Title, if not auto-generated by Logseq, is just the title of note. Category is something for my website; I have Zettelkasten, blog, info, art, stuff like that. Then of course I have tags.

Next is where I write the actual note. To reiterate: this is not me rewriting something in my own words. This is my interpretation of something. This is me creating my own ideas in conversation with something else.7

I usually include the quotation I’m interacting with as a Markdown quotation, and I use Markdown footnotes to source it.

If the note is a Folgezettel, I link the parent note.

Then, I put this note in conversation with other notes in my Zettelkasten. This is where a lot of the direct linking between my notes happens.

Step 3: Ouroboros

Just because they’re “permanent” notes, it doesn’t mean they can’t change. My Zettelkasten is a living thing that grows and changes. I can revisit notes and make new connections. I can break a note up into multiple new notes.

When I see I have enough notes on a topic, I can create something about it. That thing I create can inform other notes and inspire new notes.

The ouroboros is a mythical serpent eating its own tail. It shows up in many different cultures and belief systems. A common meaning of the ouroboros is that of cyclical renewal, death and rebirth.

My Zettelkasten is always in a state of flux, death, and rebirth. It is not static. Like the ouroboros, it feeds itself with itself. However, it is not autopoietic, a self-sustaining/creating system. My Zettelkasten is sympoietic, a system deeply intertwingled with external information.

Tensions Between Zettelkasten & the Productivity Scene by Bob Doto ↩︎

Obligatory “I Took the Building a Second Brain Course” Post ↩︎

I call Archives my Attic instead: archives and attics ↩︎

What is a Literature Note? by Bob Doto ↩︎

Folgezettel is More than Mechanism by Bob Doto ↩︎

Prefer note titles with complete phrases to sharpen claims by Andy Matuschak ↩︎

Quotes are Not Notes: Creating a Zettelkasten of Ideas by Bob Doto ↩︎